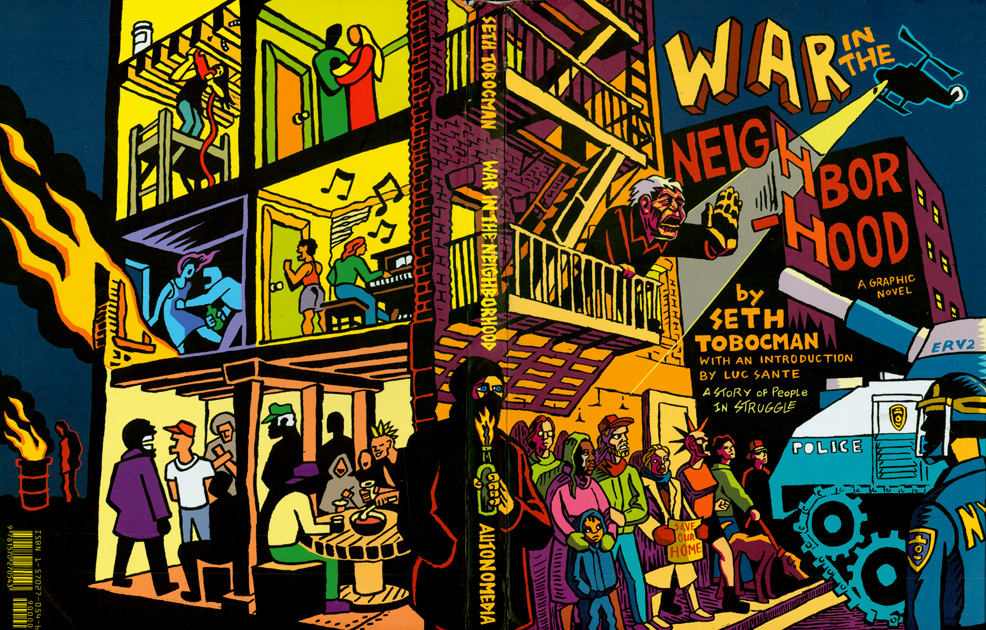

BOOK REVIEW Seth Tobocman “War in the Neighborhood” 2nd Edition, Ad Astra Comix, 2016. Paperback.

“When will we have a movement that renovates people as well as buildings?”

Seth Tobocman, War in the Neighborhood Ad Astra Comix, 2016 re-issue. Paperback. 328 pages. First published by Autonomedia, 2000.

BOOK REVIEW by Alan W. Moore

((Download the review in zine format here)

(Pre-order the book here)

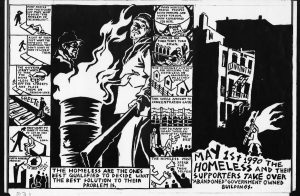

My copy of Seth Tobocman’s War in the Neighborhood stands up on my desk, right beside the poster Yoko Ono publishes in the New York Times every year around New Year. “War Is Over if you want it.” But the kind of war Seth is describing is never over, want it or not. It’s the unceasing war of the better off against the poor, and Tobocman’s War tells the story of a time when the poor fought back. The neighborhood in question is Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the 1980s and 1990s. It was when gentrification was really sinking its teeth into the housing stock, and the City of New York was executing auction sales of hundreds of vacant buildings and empty lots it had seized for default of taxes. No new public housing was being built, and the steady stream of low income tenants out of the area was becoming an exodus. Analyses of the contemporary process of inner city development had just begun to be developed (cf. Neil Smith). But already determined bands of people resisted by occupying many of those buildings and living in them – squatters.

Seth Tobocman is an artist, and “War in the Neighborhood” is a graphic novel. It is ostensibly a work of fiction. If it were a movie however, it would be a docu-drama. He based it on personal experience in the Lower East Side squatting movement and extensive research and interviews. The book is a masterpiece of squatter literature. More than any textual production, War in the Neighborhood reaches out and grips the reader, regardless of language (although translation of the text should be the next step!). It describes the political and emotional project of squatting, the milieu in its utopian and dystopian moments with all the force of graphic art. Tobocman is a master of tension and fear, outrage and reaction. This book contains some of the strongest images of solidarity in the face of repression that I have seen. In this, it is a classic work of left art in the age of neoliberalism, when reappropriation of the spaces of the “redundant” urban working classes and extreme rent-seeking has become the basis for amassing great wealth.

Resistance is necessary, law doesn’t work. On this and other issues, Tobocman is one of the world’s best propagandists for direct action. His raw-limned dramatic images of squatting, resistance and solidarity have been used by activists and collectives around the world to advertise their projects. For sure he’s not the only New York movement artist whose work on squatting gets around – Eric Drooker’s work is softer and more idealized, with classical allusions, while Fly Orr’s outsider-y graphics and symbols have an antic quality. But Seth’s work is pure politics.

This political edge, the resolve behind the line is a large part of what makes War in the Neighborhood such a great work of art. As much or more is its humanity, its subtle understanding of personality and human damage going into and coming out of political struggle, and its penetration into the spheres of the domestic. Oddly, very little written by or about squatting and squatters goes down that road (in English; in German there’s much more). This very oscillation between public and private has been a fulcrum of recent academic research into squatting (e.g. Lynn Owens Cracking Under Pressure: Narrating the Decline of the Amsterdam Squatters Movement Penn State, 2009)

The book starts with the story of a young couple, familiar with squatting from experience in England, who move into a vacant building. A group of people burst into their apartment, and demand that they leave – the building, they say, has already been claimed. What’s up? Tobocman gives a few-page history of exploitation and radical reaction on the Lower East Side. He tells the story of arson, abandonment and city housing programs designed to fail. (The “urban homesteading” program he describes was a reaction to an earlier wave of squatting, and effectively ended it.) Jane and John must build support to protect their building from a thug eviction.

The next chapter deals with the well-remembered Tompkins Square Park riot of 1988, building the story through the eyes of one dog-walking resident. After a conversation with his talking dog (!), Steve ends up in front of a picket line facing the cops. Throughout the night of rioting – provoked by out-of-town police, as later court cases proved – Steve meets the homeless encamped in the park who stay weirdly unmolested throughout the riot. Tobocman unfolds a dense, complex event and its aftermath through his succinct narrative, which is centered on the boy and his dog. Finally, Steve is beaten at a demo in the park by right-wing skinheads as cops (and tough-talking left radicals) stand by. He is alone as everyone is turning into pigs, including himself as he considers copping out on a court case seeking justice.

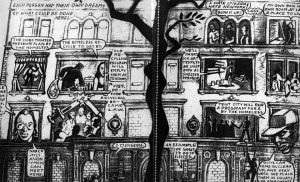

The next chapter looks at one building, one of many squatted on one street. Written as a full-dress comic book adventure (it originally appeared in the glossy alt-comic mag Heavy Metal), “The Tragedy of 319 East 8th Street” features people turning into skeletons – arsonists, police, doctors, drug dealers, bureaucrats – as they deliver mortally threatening messages to the characters. This chapter includes a brilliantly condensed vignette on the Puerto Rican griot poet Jorge Brandon, an important figure in the place many call Loisaida. Dotted throughout War in the Neighborhood are real-life characters like Clayton Patterson, Frank Morales, Michael Shenker, John Penley and more. Most are not named, but they are depicted in recognizable likenesses. Several pages depict the squatters’ resistance through the courtrooms, their own meetings, the surrounding of the building by cops, various characters’ vacillations and flashes of heroism. It’s a tangled tale, with every step fraught with tension both inner and outer. In the end, the squatters lose the building, an experience which leads to their intransigent position against negotiation – “No deal!”

Chapter four tells the story of the “Tent City” homeless people’s encampment in Tompkins Square Park which was extant when the riot happened in 1988. Seth’s voice for this story is Ron Casanova, Black, Puerto Rican, and an important homeless and anti-poverty activist. Casanova rose up during the Reagan 1980s when homelessness was epidemic in New York City. (He tells his own story in Each One Teach One: Up and Out of Poverty, Memoirs of a Street Activist with Stephen Blackburn, Northwestern University Press, 1996.) Corruption in the homeless shelters is carefully described, as well as a NIMBY-based anti-homeless meeting. These rough truths are told not with statistics and explication, but through vignettes of the organizers who moved against these injustices.

Not only in this chapter, but throughout, accounts in War are attentive to history. The “Tent City” chapter begins with a quote from homeless youth in 1933, and references 19th century land occupations in New York City. Luc Sante introduces the original publication of War. He wrote Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991), a book which lays out the centuries-long tradition – nay, industry – in the Empire City of deceiving and robbing visitors. (Not sure if this introduction is retained in the planned reprint.)

“Tent City” is at moments inspiring, when it tells of black-white solidarity, and depressing when it recounts betrayals and apathy on the part of white leftists towards the homeless activists when the shit on the street goes down. But this chapter of War soon leaves the conflicted scene of the Lower East Side to recount the story of Tent City’s march on Washington – on foot! The march was hard, and in the end politicians lied to them. But it changed lives, as Seth shows. This kind of poor peoples’ organizing – a feature of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s movement in its later days – has not been seen recently in the U.S.A., and it is important to be reminded that indeed it existed in the days of Reagan. Going forward, the organization Picture the Homeless in New York has continued to press for rights and dignity for the homeless, working in tandem with international housing rights organizations, just as the Tent City activists did 20 years before them in their presence at the U.N. (as Seth recounts).

Chapter five is the story of another squat which underwent a harrowing and dangerous eviction and demolition. Again, although it’s a “historical fiction,” It is likely closely based on fact. This time the author himself is a main character. To prove his credibility within the movement, Seth moves out of his apartment into a squat – called Deadlock House. (This place provides situations for succeeding stories in the book as well.) The residents are diverse – “a low budget version of the United Nations” – but thrown together in the face of cruel police harrassment. They hide in their building when police come to evict them; the cops bring dogs to sniff them out. In the deserted building, the author confronts himself on questions of cowardice and bravery, and “personal honor” (as he holds his cock to take a piss in a bucket). He dreams the house itself is rising up to defend itself against the cops, in virtuoso panels of political surrealism. A key character among the resistant squatters – “gargoyles” in the dream sequence – is Rage, a man who declares he will die rather than be evicted. When the cops back off, Rage goes crazy from the stress, and throws a hatchet at the author. Finally, Seth realizes, he has faced intimidation his whole life; being a squatter has taught him how to face up to it.

“Fortress of the Spirit,” chapter six, tells the story of the short-lived ABC Community Center. This was intended not only as a squat for housing but to be a social center, a large-building occupation providing many services. These are spelled out in a double-page spread. They echo the formations in many a squatted European social center – free clothing store, political art space, recycling program, “hobo theater” group, temporary housing for homeless, and a needle exchange for drug addicts. The former public school building is christened like a ship by Jorge Brandon, but runs into “stormy seas” with two Democratic mayors (Ed Koch and David Dinkins) blowing gale force winds.

There are contradictions from the start as the needle exchange activist who faces off the non-profit scheduled to receive the building from the city is revealed to be himself a coke addict. Homeless people had a significant presence in ABC. “Many of the homeless in the [Tompkins Square] park had drug problems, prison records. The sidewalks don’t make many saints, but they do produce some heroes. And in 1989 homeless Americans were standing up, organizing as a class.” Tobocman tells a love story, shows a dramatic disruption of a community board meeting (constituted advisory groups with unelected members), and tells the beginning of the complex story of the eviction.

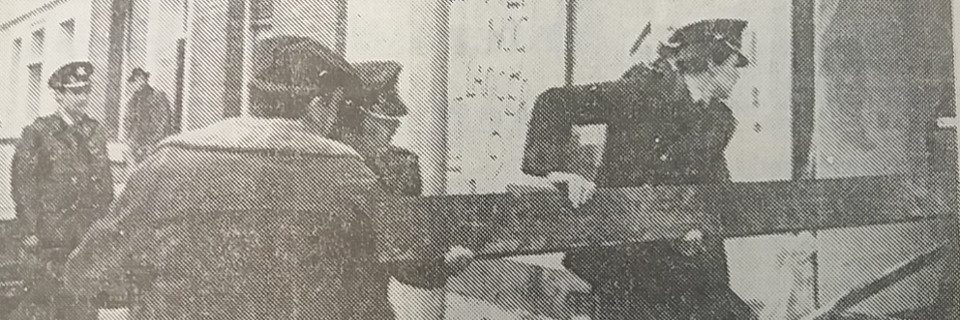

“Go ahead. Hit me in the head!,” one squatter tells a city worker preparing to bust down the door. “You might as well if yer evicting this house.” The worker flees. Say what you will of the mental stability of many of the Lower East Side squatters, this kind of full tilt dedication, heedless of personal risk, is what made the movement so powerful.

A solidarity camp arose across the street from the besieged social center. “Fuck da police/ Comin’ straight from da underground,” from the rap group NWA, plays on the boombox. Little kids chase some of the squatters on the street throwing stones at them and calling them communists. Skinheads attack another group – “help arrived in the form of a molotov cocktail,” and the skinheads run off. They don’t like to be called ‘nazis,’ another activist explains, because a lot of them are Jewish.

One of the most poignant monkey wrenches thrown into this dramatic story of populist organizing concerns the struggle over gender relations. The feminism born of abuse meets the patriarchy sprung from deprivation and thwarted lives. “One thing is for sure,” Seth writes, “being barricaded into ABC with a group of macho homeless men, many of whom were ex-cons, was a stifling and intimidating experience for some of the women.” That’s part of it. The RCP takeover is part of it (Revolutionary Communist Party). As is bitter cold, and a Christmas party in a squat barricaded by police. But Tobocman includes some pages of portraits of individual homeless people involved in the struggle for ABC in which they tell of their pride to be involved and their reasons and dreams. In the end, the occupation wears down with the cold and infighting. City officials try to strike a deal, and then in the end evict the center. The experience, Seth realizes, has marked him and the others for life. ABC as a ship is seen floating in the clouds; it will “always live in our hearts.”

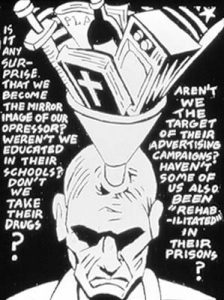

The next chapter again concerns Seth’s own “Deadlock House.” Much of the story revolves around the divides between white and black squatters. The whites include Europeans – “the European” and her friends, casual heroin users. Many of the blacks were active in the Tompkins Square Park Tent City, and their drug use is looked on as more heinous than that of the whites. In his concluding pages Tobocman writes: “We tried to build a movement of diverse people united by a common need for housing. But our distrust for each other undermined our best efforts. The cop in our head” – (represented by a skeleton running a control panel with wires into each of the main characters’ skulls) – represses us better than any police force…. When will we have a movement that renovates people as well as buildings?”

“Memorial Day Provocation,” chapter 8, is the story of a riot in the park three years after the famous one of 1988. It was provoked by the police murder of a young black artist, Grady Alexis, and another beating of a black man in full view of denizens of the park. This one went awry when a local store was looted. The City under Mayor Dinkins used the event as an excuse to close the large 10+ acre park entirely for over a year, for “renovation,” The historic bandshell in the center of the park, home to free concerts by many famous artists, was demolished. A resistant activist was caught and tortured by police. The closing of the park and the end of the bandshell spells the demise of the neighborhood as it had been. Gerrymandering reconfigures the district as part of a richer area. A right-wing councilman is elected. The Lower East Side Seth has known is over…

Chapter 9 “Kicking in Joan’s Door” is a depressing tale of sexual violence and intimidation which eventually divides a squat. It is the last chapter in the artist’s life in “Deadlock House,” and it isn’t pretty. Chapter 10 is more straightforwardly historical, built as it is with photographs and text. The last one is a kind of coda that interweaves a frankly told ideology of resistance, and a deeply felt self-knowledge born of defeat.

The graphic novel is a form that still suffers from sidelining in the hierarchy of literary genres. Seth Tobocman developed this book over many years, running chapters of it in the “comic book” graphic art and literary journal he ran with friends called World War III. To call it a ‘graphic novel’ is to really seek to elevate this genre to the level of the more privileged text-only work of literature. In fact, it might more properly be called an artist’s book. As such, it is a fusion of image and word that effectively accomplishes what neither can do alone.

War in the Neighborhood tells stories particular to the Lower East Side, but the conflicts described will surely be familiar to squatters all over the world. The Lower East Side squatters’ movement was raw populist organizing. Old school anarchist direct action emerged from real need, made spectacularly public through homelessness. The movement unfolded in a fog of drugs (its own kind of war, as defined by the government). The squatters themselves saw the aims and values of their movement through a scrim of class and gender, with continual misperceptions, oppression-bruised sexualities and incommensurable lifestyles clashing continually. The movement was based not in the needs of laboring people, but in the needs of any people for housing, pure and simple. This is the kind of struggle that is emerging globally with the migration crises of our day, and one in which political squatters are taking an active role.* And the differences among those who take part are as sharp as any told in War.

Written by Alan W. Moore

*(See the new anthology produced with the SqEK group and edited by Pierpaolo Mudu & Sutapa Chattopadhyay, Migration, Squatting and Radical Autonomy Routledge, 2016)

Thank you, nice read.